Reactive Tweets with Elixir GenStage

GenStage & back-pressure

Last july, José Valim, the creator of the Elixir programming language, announced GenStage, a new behaviour for exchanging events with back-pressure between processes.

I’m not going to explain how GenStage works, there are already plenty of articles and videos on the subject (the latest being José’s keynote at the Elixir Conf 2016).

Instead, we will focus on one fundamental (and maybe the most important) aspect of GenStage, that is, how it provides back-pressure to prevent downstream stages from receiving more message than they could handle.

Handling streams of data—especially “live” data whose volume is not predetermined—requires special care in an asynchronous system. The most prominent issue is that resource consumption needs to be controlled such that a fast data source does not overwhelm the stream destination. — reactive-streams project

In the Erlang world, the BEAM does not implicitly support back-pressure. If a process receives more messages than it can process, it will require more and more memory, crashing the virtual machine in the long term. This is a problem left to the developer.

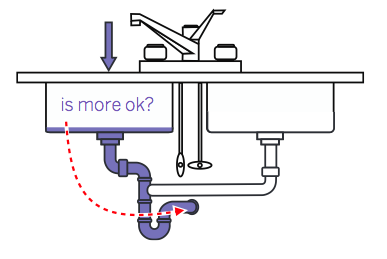

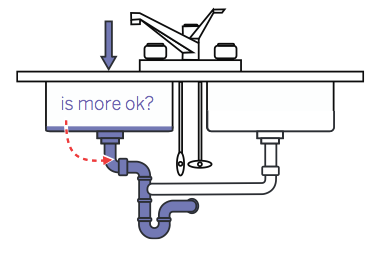

To understand the problematic from a different perspective, let’s take a great metaphoric example borrowed from Fred Hébert’s article Queues Don’t Fix Overload.

You should definitely check our the original article, Fred is the author of Erlang in Anger and his writings are always a real pleasure to read.

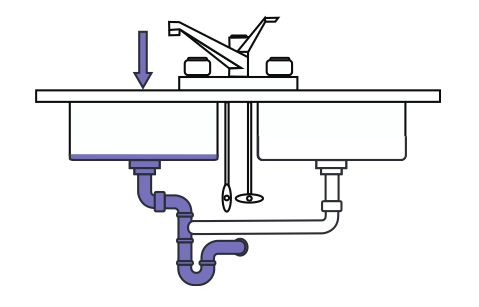

Under normal load, your system handles the data that comes in, and carry it out fine.

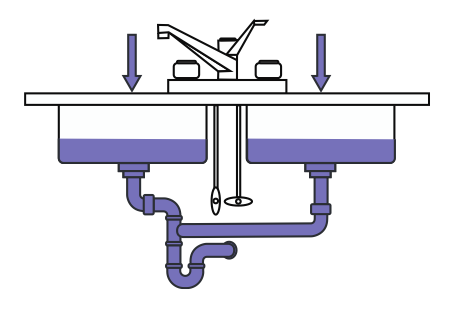

However, from time to time, you’ll see temporary overload on your system.

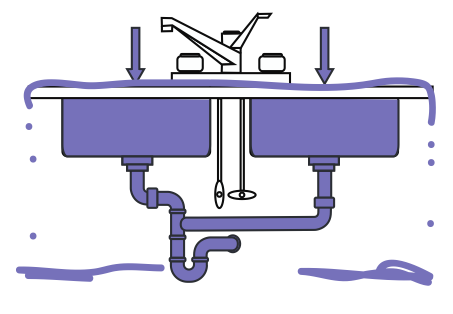

When you inevitably encounter prolonged overload, the system crashes.

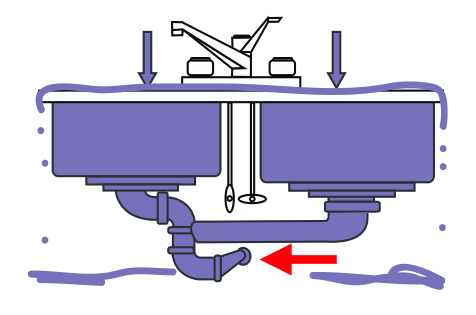

This is of course an oversimplification of the problems we might encounter with message passing but in the end this reflects pretty much what’s going to happen if we do not design our systems with back-pressure in mind.

How can we prevent this to happen? First, we must identify the bottleneck.

Then, we have to find a way to prevent the process’s message-queue to grow indefinitely.

OTP provides a lot of constructs to work around this problem, using GenServer.call/3 for example, provides a way to apply back-pressure: Instead of only sending the message, the caller have to wait for the response from the server, when the server is overloaded and does not respond in a given period of time, the call fails with a timeout error.

An even better solution would be to adjust the producer throughput to the consumer demand, this way we could ensure that each stage is never overloaded.

Actually, GenStage takes a very similar approach but instead of having the producer asking the consumer before pushing events, it follows a more demand driven approach:

To start the flow of events, we subscribe consumers to producers. Once the communication channel between them is established, consumers will ask the producers for events. We typically say the consumer is sending demand upstream. Once demand arrives, the producer will emit items, never emitting more items than the consumer asked for. This provides a back-pressure mechanism. — GenStage documentation

With these concepts in mind, let’s implement a Twitter streaming GenStage producer.

Twitter streaming producer

Using the Twitter streaming API is very straight-forward. It returns an infinite stream of JSON Tweets each of them prefixed with a delimiter representing the length of the Tweet:

1

2

3

4

5

6

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

1953

{"retweet_count":0,"text":"Man I like me some @twitterapi","entities":{"urls":[],"hashtags":[],"user_mentions":[{"indices":[19,30],"name":"Twitter API","id":6253282,"screen_name":"twitterapi","id_str":"6253282"}]},"retweeted":false,"in_reply_to_status_id_str":null,"place":null,"in_reply_to_user_id_str":null,"coordinates":null,"source":"web","in_reply_to_screen_name":null,"in_reply_to_user_id":null,"in_reply_to_status_id":null,"favorited":false,"contributors":null,"geo":null,"truncated":false,"created_at":"Wed Feb 29 19:42:02 +0000 2012","user":{"is_translator":false,"follow_request_sent":null,"statuses_count":142,"profile_background_color":"C0DEED","default_profile":false,"lang":"en","notifications":null,"profile_background_tile":true,"location":"","profile_sidebar_fill_color":"ffffff","followers_count":8,"profile_image_url":"http:\/\/a1.twimg.com\/profile_images\/1540298033\/phatkicks_normal.jpg","contributors_enabled":false,"profile_background_image_url_https":"https:\/\/si0.twimg.com\/profile_background_images\/365782739\/doof.jpg","description":"I am just a testing account, following me probably won't gain you very much","following":null,"profile_sidebar_border_color":"C0DEED","profile_image_url_https":"https:\/\/si0.twimg.com\/profile_images\/1540298033\/phatkicks_normal.jpg","default_profile_image":false,"show_all_inline_media":false,"verified":false,"profile_use_background_image":true,"favourites_count":1,"friends_count":5,"profile_text_color":"333333","protected":false,"profile_background_image_url":"http:\/\/a3.twimg.com\/profile_background_images\/365782739\/doof.jpg","time_zone":"Pacific Time (US & Canada)","created_at":"Fri Sep 09 16:13:20 +0000 2011","name":"fakekurrik","geo_enabled":true,"profile_link_color":"0084B4","url":"http:\/\/blog.roomanna.com","id":370773112,"id_str":"370773112","listed_count":0,"utc_offset":-28800,"screen_name":"fakekurrik"},"id":174942523154894848,"id_str":"174942523154894848"}

The 1953 indicates how many bytes to get the rest of the Tweet (including \r\n).

We will use Twittex, a Twitter client application I wrote a while ago for learning purposes. It supports OAuth1 and OAuth2 and provides a wrapper for the Twitter API.

Twittex depends on :hackney, an HTTP library for Erlang. The latter has the capability to stream the response to a given process which will simplify our task a lot.

Implementing the GenStage behaviour

Implementing a GenStage behaviour is very simple, this is because the act of dispatching the data and providing back-pressure is completely abstracted away from the developer:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

defmodule TwitterStream do

use GenStage

def start_link(options \\ []), do: GenStage.start_link(__MODULE__, [], options)

defdelegate stop(stage, reason \\ :normal, timeout \\ :infinity), to: GenStage

@impl true

def init([]), do: {:producer, %{ref: nil, demand: 0, buffer: "", buffer_size: 0}}

We define our state in the init/1 callback, it provides following fields:

:ref— Reference to the:hackneyHTTP response.:demand— Actual demand.:buffer— Used to store a partial Tweet until we get more data.:buffer_size— Number of bytes until next Tweet.

We will see why we need :buffer and :buffer_size later. First, let’s handle the demand for our producer (check the documentation for more details):

1

2

3

4

def handle_demand(demand, state) do

if state.demand == 0, do: :hackney.stream_next(state.ref)

{:noreply, [], %{state | demand: state.demand + demand}}

end

The handle_demand/2 callback increments the :demand state. If the current demand is 0, it will also fetch the next chunk of data using :hackney.stream_next/1.

Handling HTTP response messages

Next, we have to handle :hackney_response messages:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

def handle_info({:hackney_response, ref, {:status, status_code, reason}}, state) do

if status_code in 200..299 do

if state.demand > 0, do: :hackney.stream_next(ref)

{:noreply, [], %{state | ref: ref}}

else

{:stop, reason, state}

end

end

def handle_info({:hackney_response, _ref, {:headers, _headers}}, state) do

:hackney.stream_next(state.ref)

{:noreply, [], state}

end

def handle_info({:hackney_response, _ref, chunk}, state) when is_binary(chunk) do

chunk_size = byte_size(chunk)

cond do

state.buffer_size == 0 ->

:hackney.stream_next(state.ref)

case String.split(chunk, "\r\n", parts: 2) do

[size, chunk] ->

{:noreply, [], %{state | buffer: chunk, buffer_size: String.to_integer(size) - byte_size(chunk)}}

_ ->

{:noreply, [], state}

end

state.buffer_size > chunk_size ->

:hackney.stream_next(state.ref)

{:noreply, [], %{state | buffer: state.buffer <> chunk, buffer_size: state.buffer_size - chunk_size}}

state.buffer_size == chunk_size ->

if state.demand > 0, do: :hackney.stream_next(state.ref)

event = Poison.decode!(state.buffer <> chunk)

{:noreply, [event], %{state | buffer: "", buffer_size: 0, demand: max(0, state.demand - 1)}}

end

end

def handle_info({:hackney_response, _ref, :done}, state) do

{:stop, "Connection Closed", state}

end

def handle_info({:hackney_response, _ref, {:error, reason}}, state) do

{:stop, reason, state}

end

There are five types of :hackney_response messages, the first we receive is :status, we use it to store the message ref into our state.

The second is :headers, it is not important in our case.

After that, we will receive chunks of data until the response is :done or an :error occurs. We have to process those chunks of data in order to extract each Tweet and send it downstream to our consumer(s).

This is the reason we need to store the current :buffer and :buffer_size. We use the delimiter value to know how many bytes to read off of the stream until the next Tweet. Basically, we have to call :hackney.stream_next/1 until the Tweet is completely buffered.

Have a look at the third handle_info/2 function implementation. It is a bit tricky but actually, it is not that hard to understand.

The last thing we have to implement in our module is a way to tell :hackney to stop streaming more data. Of course, the best place to do that is in the terminate/2 callback:

1

2

3

def terminate(_reason, state) do

:hackney.stop_async(state.ref)

end

When we call stop/1, we close the connection before shutting down the stage process. :hackney provides a stop_async/1 function which does exactly that.

Applying back-pressure

Now, I started this post with a long introduction about how back-pressure is important. I told you that if you don’t take special care about it, bad things would happen.

During the implementation of our stage, we did not talk a single time about this issue. Indeed, back-pressure is already been applied. You might have asked yourself why we call :hackney.stream_next/1 in almost every function. Right?

In our implementation, the stage is the consumer of the :hackney stream and uses stream_next/1 to control the throughput of data to process. Because we check the current demand before fetching more data, we have the Twitter stream tidily coupled to the stage demand. In other words, we are applying back-pressure at the TCP level …

Yes, that’s right, we are pushing the boundaries outside the BEAM and even outside of our local machine. If our consumer is too slow to process the stream of incoming data, our stages will stop calling stream_next/1 which will automatically prevent the underlying operating system from acknowledging more TCP packages. In the end, the Twitter streaming server will stop sending us more data until we are able to process them.

Putting the parts together

Our GenStage Twitter streaming producer is ready. You may have noticed that we never made the HTTP request to the API endpoint nor did we tell :hackney to send us the response. Let’s see how to do that:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

def twitter_samples do

{:ok, stage} = TwitterStream.start_link()

# [stream_to: stage] tells hackney to send the stream to our stage

# [async: :once] tells hackney that we will control the flow with :stream_next/1

conn_opts = [hackney: [stream_to: stage, async: :once], recv_timeout: :infinity]

url = "https://stream.twitter.com/1.1/statuses/sample.json?delimited=length"

case Twittex.API.request(:post, url, [], [], conn_opts) do

{:ok, %HTTPoison.AsyncResponse{}} ->

{:ok, stage}

{:error, error} ->

Stream.stop(stage)

{:error, error}

end

end

Finally, we can connect a consumer to actually do something with our stream. In the following example, we only print the text of each Tweet:

1

2

3

4

5

{:ok, stage} = twitter_samples()

GenStage.stream([stage])

|> Stream.map(&Map.get(&1, "text"))

|> Stream.each(&IO.inspect/1)

|> Stream.run()

Going a step further

We can even go a step further and write a more complex examples using Flow.

For example, to show the top 25 hashtags of multiple Twitter streams at a regular time interval:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

~w(trump hillary)

|> Enum.map(&Twittex.Client.stream!(&1, stage: true))

|> Flow.from_stages()

|> Flow.flat_map(& &1["entities"]["hashtags"])

|> Flow.map(& &1["text"])

|> Flow.partition(window: Flow.Window.periodic(5, :minute))

|> Flow.reduce(&Map.new/0, fn word, acc -> Map.update(acc, word, 1, & &1 + 1) end)

|> Flow.departition(&Map.new/0, &Map.merge(&2, &1, fn _, v1, v2 -> v1 + v2 end), & &1)

|> Enum.each(fn map ->

IEx.Helpers.clear

map

|> Enum.sort_by(&elem(&1, 1), &>/2)

|> Enum.take(25)

|> Enum.each(fn {hashtag, count} ->

IO.puts [IO.ANSI.bright, String.pad_leading(Integer.to_string(count), 3, " "),

IO.ANSI.reset, " ##{hashtag}"]

end)

end)

Flow makes it fairly simple to pipe incoming data into multiple stages (in a similar way we would use Enum or Stream), with

the benefit of levering concurrency.